I drive my car regularly between my home and lab. But one day, deep in my thoughts while driving, I suddenly found a speed breaker had cropped up overnight on my route. Although I had never encountered this obstacle before, I automatically slowed my car at the right time without explicitly thinking of changing the gear or moving my legs to different positions, and I safely crossed the obstacle.

If I ask how I responded so fast with so many concerted actions, you would probably say it’s just practice. But what does practice do? Why does it make a man perfect?

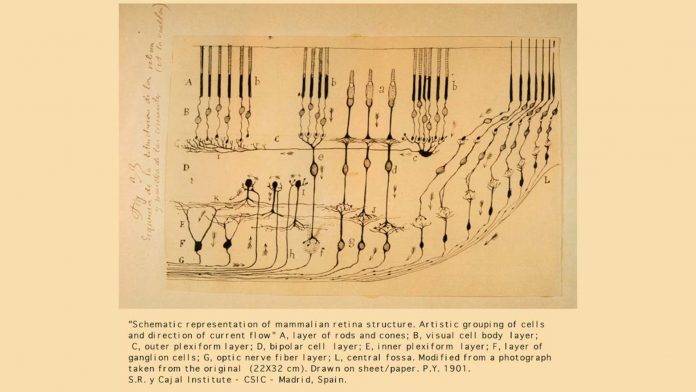

The answer to this question lies in our nervous system, which is broadly divided into two parts: the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system, comprising the brain and spinal cord, serves as the primary control centre of the body. It makes decisions, processes information, and coordinates our actions.

The peripheral nervous system consists of all the nerves that branch out from the brain and spinal cord and spread throughout the body. These nerves act like communication cables, carrying messages to the brain from our sense organs and from the brain to our muscles.

For example, when we watch a movie, our eyes detect light using special light-sensing nerve cells. These signals travel through the peripheral nerves to the brain, where the information is processed and interpreted. Once the brain decides how to respond, messages are sent back through the peripheral nervous system to specific muscles. The muscles around our eyes and face then contract or relax, allowing us to express emotions such as smiling, laughing, or even crying in response to the movie scene.

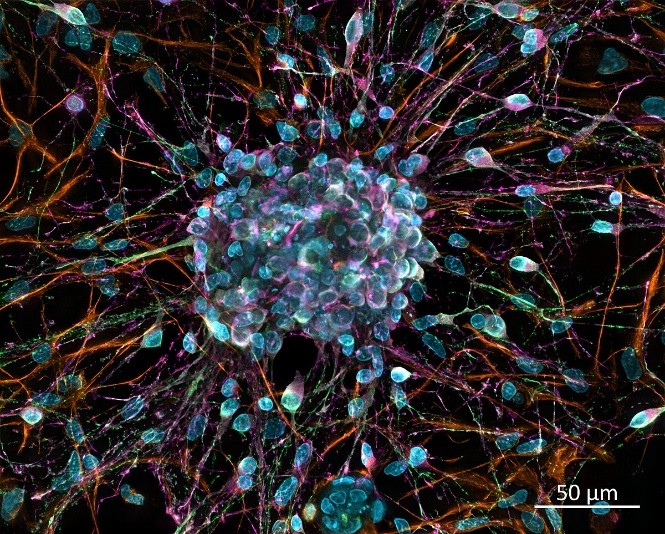

An microscopic image of network of neurons, File:Rat primary cortical neuron culture, deconvolved z-stack overlay (30614937102).jpg – Wikimedia Commons

The neurons communicate with each other using a class of small molecules called neurotransmitters that elicit electrical impulses. Glutamate, acetylcholine, GABA, serotonin, and dopamine are a few examples of neurotransmitters that transmit messages.

Neurons release neurotransmitters into the space formed between the end of a neuron and the next neuron, which is called a synapse. These neurotransmitters bind to a group of receptor proteins on the cell membrane of the receiving neurons. Upon this binding, the receptor proteins undergo structural changes that permit the flow of electrically charged ions into the neuron. This influx of ions into the neuron creates a difference of electric charges inside and outside the neuron, measured in terms of electric potential. Once a neuron crosses a certain threshold of electric potential, it is ready to pass the electrical impulse to the next neuron. Colloquially, we call it neuronal firing. A chain of neurons fires to transmit signals from the brain to the muscle and from the muscle to the brain.

Use it or lose it

Glutamate is one of the most abundantly used neurotransmitters by neurons in the central nervous system. An important class of proteins that bind to glutamate and facilitate the flow of positively charged ions into neurons are the ionotropic glutamate receptors. Glutamate and its ionotropic receptor pair are essential for the fast transmission of messages through neurons, a feature essential for training our brain to act fast.

Constant activity in a region of the brain leads to constant firing of neurons, neurotransmitter release and generation of electrical impulses. This constant firing increases the number of ionotropic glutamate receptors on the receiving neuron’s surface. The increase in the receptor reduces the time for a neuron to reach the threshold of electrical potential. It is a loop; constant firing enhances receptor levels, and increased receptor levels lead to further increases in firing. Thereby strengthening the neuronal connections for that specific action.

Let’s consider an F1 car racer; these racers are known to have very high reflexes. These drivers need to have short response times to handle obstacles in race courses. One more example, we all have seen the lightning speed of MS Dhoni’s stumping in cricket matches. All this is attributed to their intense practice sessions. But what these practice sessions do to their brains is strengthen neuronal connections in the specific brain regions. This is called long-term potentiation. The strengthened neuronal network can now transmit messages faster and more efficiently, and this produces the result that we see in competitions.

When the activity in certain regions of the brain decreases, the neurons also have less activity. For example, when you have a bad breakup, people often advise focusing on other things and letting time heal the wound. So, when you focus your energy on other positive things in life, the region that had stored memories of the relationship has very little firing due to a low-frequency activation of the receptor proteins, which leads to the reduction of these receptors on the receiving neuron’s surface. This activates the negative loop, low firing leading to lower receptor levels, and lower receptor levels lead to lower firing. This process gradually weakens the neuronal contacts in the regions and further leads to loss of memory. Viola! You forgot that bad memory. This phenomenon is called long-term depression. Next time you break up, go do something else and train your brain to forget the memory of that relationship.

In neuroscience labs, researchers study long-term potentiation and long-term depression using thin slices of mouse hippocampus kept alive in a nutrient-rich fluid bath. They place tiny electrodes to stimulate sender neurons with high-frequency bursts, typically a strong electrical pulse of short duration, in the range of milliseconds to seconds, for long-term potentiation (strengthening connections). In case of long-term depression experiments, the electrodes are programmed to deliver a weak electrical pulse for a long duration in the range of 10-15 minutes. In both cases, the electrical potentials are recorded from nearby receiving synapses. The recording timeframes can vary from hours in cultured cells to as long as a year in electrode-implanted animal models. Long-term potentiation, if successful, increases signal strength over an extended period of time, whereas long-depression decreases signal strength.

It’s all about balance

The balance between long-term potentiation and long-term depression is at the crux of how the neuronal synapses are managed in the vast network of neurons. It explains how our neurons prioritise which contacts to strengthen and which ones to retire. The neuronal connections are strengthened for a certain activity based on how often the task is repeated, and weakened based on how infrequently it is used.

The balance is impaired in many diseases related to cognition. Impaired long-term potentiation is known to play an important role in Alzheimer’s, where it leads to loss of cognition. Heightened long-term potentiation and reduced long-term depression lead to hyperactivity of neurons that induces epileptic seizures. Rivastigmine and L-DOPA are used to treat dementia in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients by inducing long-term potentiation. Memantine is used to modulate long-term depression and thereby reduce elevated neuronal firing induced neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s patients.

The structural details of ionotropic glutamate receptors, among others, are slowly being deciphered. Since isolating these receptors from cells is a challenging task, and the structural changes in the receptors upon glutamate binding happen within milliseconds, making it difficult to capture the receptor during the transition. Structures of receptors in the absence of glutamate are currently available, and the research to determine the receptor’s structural transition is ongoing. These understandings would enable us to design therapeutics that could specifically modulate the receptor activity and thereby treat cognitive defects caused by deregulation of long-term potentiation and long-term depression.

And, for me, who has to drive while thinking about my experiments, I trust my neuronal connections to have strengthened, to allow me to act fast enough to navigate the ever-changing Hyderabad roads. Kary Mullis, the 1993 Chemistry Nobel Laureate for his discovery of the polymerase chain reaction, had actually conceived his Nobel-winning experiments while driving his car. If he can, maybe I can too!