Imagine buying a warm, lightweight shawl sold as “A grade Pashmina” in the market, only to learn that it cost the lives of thousands of Tibetan antelopes. For years, traders, enforcement agencies and experts struggled to tell apart legal pashmina from illegal Shahtoosh. Now, a simple PCR test developed at CCMB can reveal the truth…from just a few strands!

The development of the textile industry can be traced back to pre-historic times when early humans used natural fibres like flax, cotton and wool to develop rudimentary clothing. As civilizations developed, the industry diversified based on the source of raw material, the technique of fibre preparation and the complexity of weaving and dyeing practices. This diversification not only set the stage for specialised textile industries around the world but also correlated certain fibres with wealth, power and identity. “Shahtoosh”, popularly called the “king of wools” is one such example.

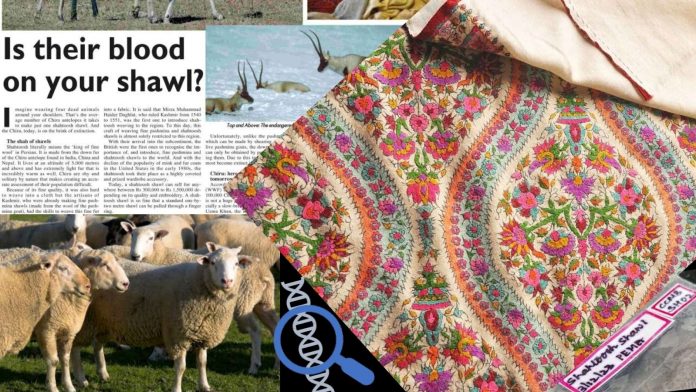

Obtained from the undercoat of Pantholops hodgsonii, commonly known as Chiru or Tibetan Antelope, Shahtoosh has been a treasured commodity amongst the royalty, nobility and other elite patrons. Gradually, the exclusivity and prestige associated with this historical fibre garnered strong attention from the rich and wealthy leading to its increasing demand in the market. Unfortunately, to obtain a substantial amount of Shahtoosh, thousands of Chiru need to be killed and skinned. This led to massive poaching and near extinction of the species.

Chiru is found on the remote Tibetan plateau and in the Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces of western China. They live at high altitudes with an average annual temperature of -4°C and harsh blizzards. Because of their habitat preference, all attempts of domestication failed, leaving poaching as the only option. Previously, nomads of the Tibetan plateaus killed Chiru for meat and sold the undercoat for profit. However, in the 1980s, when the Tibetan plateau was opened for mining, spotting the animal became easier and when poachers found the breeding grounds of Chiru, mass killing began and a trafficking chain was established. In the mid-1980s, Shahtoosh was smuggled from China to India and Nepal on a barter basis. In exchange for fibre, Indian traffickers supplied tiger body parts and animal skins. In India, Shahtoosh was delivered to Kashmir, a long-established hub of artisans and craftsmen skilled in the art of shawl-making. Here, the fibre was intricately woven into shawls and sold in the international market at around $US 20,000 per shawl.

Chiru or Tibetan antelope, PC: Marc Faucher: https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/27823297

To protect the Chiru population, the international community and national governments took several actions. In 1979, the Chiru was listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This listing ensured that strictest protection was given to the animal under international law, prohibiting the international trade of Shahtoosh shawls. The Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972 completely bans the hunting of Chiru and the production or sale of Shahtoosh. While the Governments in India, China and Nepal have implemented stricter penalties for poaching and smuggling, CITES regulations enable penalizing traders, buyers and consumers of Shahtoosh. While this ban severely affected the livelihood of generational Shahtoosh-crafting communities, it also had a negative impact on Pashmina trade! But why?

Goats in Ladakh whose undercoat is used to make Pashmina wool, PC: Karthikeyan Vasudevan

Pashmina trade of India, another renowned textile heritage, has lost value in the international market due to adulteration issues. Pashmina wool comes from the undercoat of a domesticated goat, Capra hicus, found in the arid Himalayan plateau at 12,000-14,000 feet. This wool can be shorn or combed out annually but the yield of high-quality Pasmina is quite low. So, suppliers adopted two distinct adulteration strategies. First is mixing Pashmina with Shahtoosh and selling it as A grade/ Superfine Pashmina which increases its price multi-fold in the international market. However, when seized by CITES, and the origin of the commodity is tracked to India, a CBI investigation is set up and all related establishments are sealed, goods confiscated and individuals fined or jailed. Second is mixing Pashmina with Angora and Merino which dilutes the quality of fabric in terms of fibre fineness, warmth and durability. While these adulterations harm the trust in authentic Indian traders and Indian craftsmanship, the presence of Shahtoosh carries significant legal and conservation implications.

The traditional Shahtoosh detection method relies on observing fibre morphology under a light microscope. It is slow and subjective, often disrupting trade and discouraging honest traders. The resulting socio-economic impact in Kashmir led the traders to approach Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in 2021 for a rapid and foolproof alternative. Dr. Karthikeyan Vasudevan’s team at CCMB’s Laboratory for Conservation of Endangered Species (LaCONES) responded by turning to DNA preserved within the fibre. How?

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a sensitive molecular test that can detect even trace amounts of DNA. It works via amplifying and identifying specific regions of DNA. But fibre processing breaks DNA into short pieces. If they are too short, it might be broken between the two ends of the DNA region of interest. In such cases, PCR fails. To circumvent this problem, Dr Vasudevan’s team looked into mitochondrial DNA in the fibre.

Animal fibres like hair or fleece have two parts: living root cells which grow upward and harden into the keratinised shaft. As they keratinize, most cellular material is lost but small amounts of mitochondrial DNA are preserved. This is due to the high number of mitochondria within hair root cells and resilient nature of keratin. Despite fibre processing, mitochondrial DNA is often in a good enough condition for a PCR detection. Using authenticated Shahtoosh samples from the Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad, the team designed a Chiru-specific PCR test.

Collection of fibres from a fabric in Salar Jung museum using a toothbrush for DNA extraction and testing, PC: Karthikeyan Vasudevan

Vasudevan’s team also uses a gentler method to extract DNA from the fibres without damaging the fabric. Unlike earlier studies that required cutting, grinding or chemically dissolving a part of the fabric or produced poor quality/quantity of DNA, Dr Vasudevan’s team uses a toothbrush for fibre collection, followed by high-efficiency DNA extraction and PCR amplification. The team has filed a patent for the technology and has offered the service to traders, exporters, government agencies and individual buyers at a nominal cost. Efforts are underway to establish a testing centre in Srinagar to improve accessibility.

At present, the PCR-based identification offers the most reliable way to authenticate fibre, protect wildlife, support genuine traders and restore trust in India’s rich Pashmina craft and heritage.