A June evening in a small town in Kerala’s Palakkad district. There’s not much to entice visitors – a single gym, perhaps two lodges, a juice and milkshake parlour. Yet, a fair share of tourists stops by for a night or two each year, laden with rucksacks, cameras and binoculars. The reason becomes clear if you take a short walk to the outskirts of town. Here, behind the acres of fields spread out in the fading daylight, a blue-green wall rises up to meet the clouds.

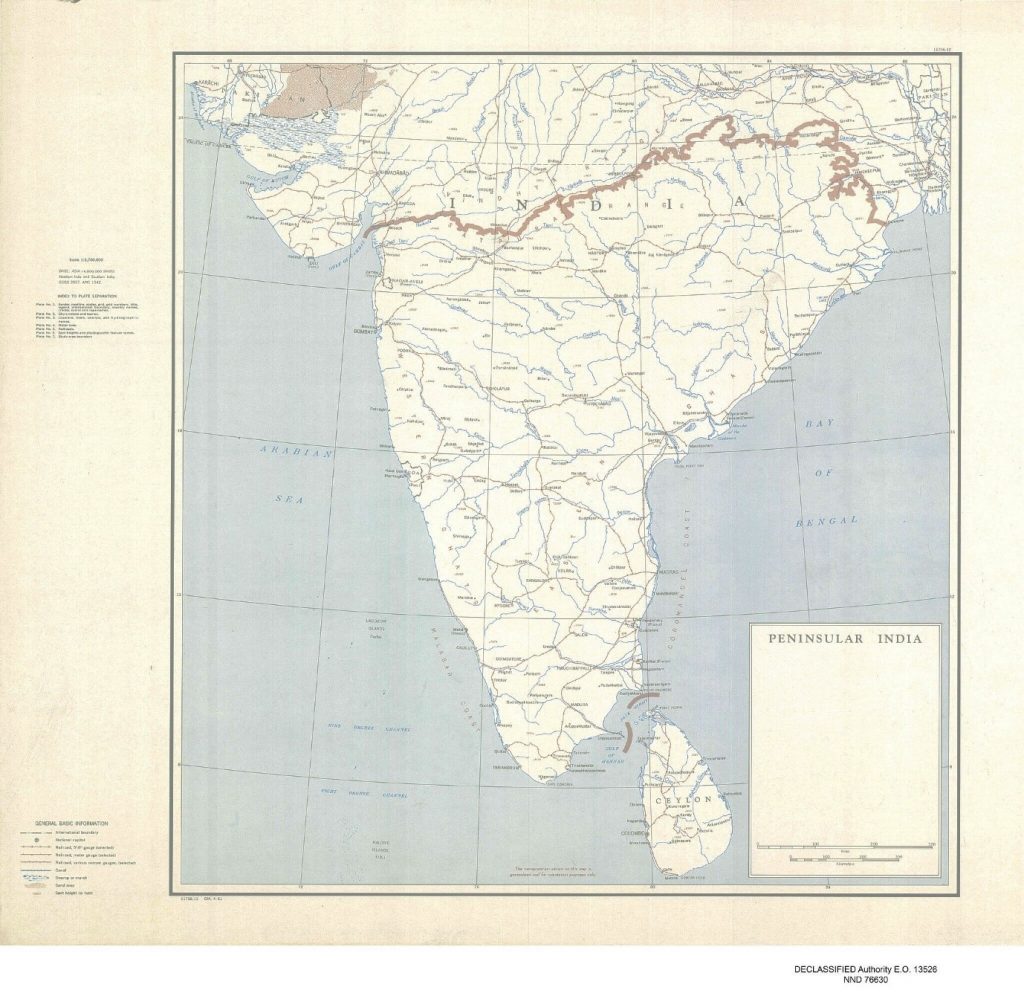

For that is what the Western Ghats can seem like to those of us used to the gentle curves of the plains – a wall of trees that is eerily silent save for the droning of the cicadas. Every year, thousands of people travel to nondescript towns and villages in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu to trek, birdwatch, film, and in cases like ours, research. What makes the Ghats a haven for nature lovers is also why we study them- it is one of the 36 ‘biodiversity hotspots’ in the world. According to the highly cited original paper, this means that it contains more than 1,500 ‘endemic’ plant species (species that are found nowhere else in the world). Furthermore, more than 70% of its forest cover has been lost, making the region a top priority for conservation biology.

So how much biodiversity does the Western Ghats really have? The research is ongoing. But, we do have estimates for some organisms – approximately 100 species of mammals (of which 11% are endemic), 200 species each of amphibians and reptiles (78 and 62% respectively are endemic), 300 species of freshwater fish (41% are endemic), 500 species of birds (4% are endemic) and 600 species of trees (56% are endemic). But for scientists interested in tropical mountain chains, the real headscratcher is this – why is there so much biodiversity in the Western Ghats, and where did it come from?

From an evolutionary biology perspective, three processes ultimately determine the distribution of biodiversity- speciation, dispersal and extinction. Speciation refers to the creation of new species from pre-existing ones, whereas dispersal is the movement of species into an area from others. Both act together to increase the number of species in a region. Alternatively, extinction, which refers to the death of a species, decreases the biodiversity of a region.

What happened in the Western Ghats:

Most of the examined animal diversity of Peninsular India (roughly below 23° N latitude), of which the Western Ghats is a part, dispersed into India within the last 65 million years, following which speciation events took place. One example is that of toads, which likely dispersed from elsewhere in Asia, with subsequent speciation probably promoted by the diverse habitats and heterogenous landform of the Ghats. A well-studied case of how speciation can be facilitated by separating organisms from each other, is the Palghat Gap: a 30-km stretch of land at 200 m elevation that cuts through the mountains (which rise to 2 km on either side). Researchers speculate that the gap has promoted the separation of populations of a single species into different species over time.

On the other hand, the Western Ghats also contains some groups of animals that have remained there since their origin! A recent study of ours’ shows that an ancient group of long-legged centipedes called scutigeromorphs have existed in the peninsular region of India for approximately 125 million years, eventually evolving into multiple species in the Western Ghats. Such species are called ‘Gondwanan relicts’ as their ancestors were present on Peninsular India back when it was attached to Africa, South America and Australia as part of the supercontinent Gondwana, more than 200 million years ago.

Certain favorable environmental conditions may have allowed both dispersers into India as well as Gondwanan relicts to persist in the Western Ghats till date. It is argued that some parts of the region, particularly south of the Palghat gap, served as ‘refugia’ as the stable environment allowed species to thrive while species elsewhere died out due to fluctuating climate or extreme climatic events. Research shows that tropical forests were once widely distributed across Peninsular India, and while they receded from most of the Deccan plateau, they remain in the southern part of the Ghats even today. Speciation, dispersal and extinction are co-occurring processes. It can be hard to tease apart which of the factors, if any, were most influential in driving the species richness of a given group of organisms in a region. Scientists use a rigorous combination of fieldwork, molecular techniques and phylogenetic analyses (techniques to understand evolutionary relationships between organisms) within a hypothesis-testing framework to bring more clarity to our understanding of the evolution of biodiversity in the Western Ghats. However, there is a bleak side to things. Uncontrolled tourism, ecologically insensitive ‘development’ and a rapidly warming planet mean that our quest for answers may not be fast enough. We are currently trudging through the sixth mass extinction, which is the only mass extinction event in the history of the world entirely caused by human activity. Species may go extinct before we have a chance to describe them and determine their distributions, much less understand their ecology and evolutionary biology. The high walls of the Western Ghats are at risk of coming down: literally, because of development activities that carve through the hills, but also metaphorically, as we lose the rich biodiversity that has survived here since millions of years before humans came into being.